- Home

- Jacqueline Firkins

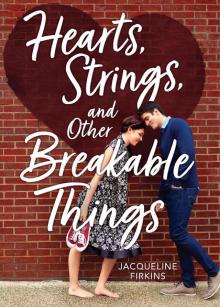

Hearts, Strings, and Other Breakable Things

Hearts, Strings, and Other Breakable Things Read online

Contents

* * *

Title Page

Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

More Books from HMH Teen

About the Author

Connect with HMH on Social Media

Copyright © 2019 by Jacqueline Firkins

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to [email protected] or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Cover photograph © 2019 Caterpillar Media, by José Márquez & David Field

Photo of girl © 2019 Getty Images/shestock

Cover design by Lisa Vega

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Firkins, Jacqueline, author.

Title: Hearts, strings, and other breakable things / Jacqueline Firkins.

Description: Boston ; New York : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2019] | Summary: Living with her aunt’s family in Mansfield, Massachusetts, for a few months before turning eighteen and starting college, Edie is torn between Sebastian, the boy next door, and playboy Henry.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019001111 (print) | LCCN 2019002954 (ebook) | ISBN 9780358156710 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328635198 (hardback)

Subjects: | CYAC: Dating (Social customs)—Fiction. | Family life—Massachusetts—Fiction. | Cousins—Fiction. | Private schools—Fiction. | Schools—Fiction. | Massachusetts—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.F553 (ebook) | LCC PZ7.1.F553 He 2019 (print) | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019001111

v1.1119

For Jane, for Jen, and for girls who sigh in window seats

Chapter One

* * *

At first the car ride was simply annoying. Edie slouched in the back seat of the SUV, clutching her mom’s sticker-coated guitar case. Her uncle Bert kept his eye on the road, characteristically quiet. Her aunt Norah blithely rattled on from the passenger seat, characteristically not so quiet. She was lost in speculation about the challenges Poor Edith would face now that she’d left foster care and come to live in “a real home.” Edie didn’t have a stable upbringing, a private education, or any exposure to society. Her wardrobe was atrocious. Her posture was appalling. She had bright orange cheese powder under her ragged fingernails, proving she had no understanding of proper diet or personal care. She was practically poisoning herself.

“And that hair!” Norah exclaimed. “Good lord, what will the neighbors say?”

Edie sank a little lower and tried to finger comb through the worst of her tangles, unsure why the neighbors would care about something as trivial as her hair. The purple dye that clung to the tips had long since faded to a subtle shade of lavender. The rest was a painfully ordinary shade of brown. It was dry and frizzy, and she hadn’t cut it for a couple years, but it was just hair.

“Don’t worry,” Bert assured Norah, drawing her attention away from the back seat. “You’ll get Edith up to snuff in no time. Why, look what you’ve done with me.”

“Yes, you’re right, of course.” Norah sighed while adjusting Bert’s shirt collar. “I do have a talent for improving people. The ladies in the club are always remarking on it.”

Edie assumed Norah was referring to her Great Hearts, Good Causes club, which she’d been boasting about lately. Since joining last summer, Norah had apparently fundraised for Nigerian schoolchildren, Syrian refugees, and hurricane victims in Puerto Rico. Now she was determined to outdo all her neighbors by displaying her Great Heart on her very own doorstep. After all, anyone could send money to “those other people.” Few had the fortitude and generosity to let a poor relation live under the same roof, almost like family.

“We’re putting you in the east room,” Norah said as Bert turned off the highway.

“The big one in the corner?” Edie blinked away her surprise.

“I know,” Norah said as if surprised, herself. “Normally we save it for guests, but we’re not expecting anyone until summer.”

Edie gripped the guitar case a little tighter as she mentally checked off yet another title she wouldn’t hold during her stay: family, guest, anyone. She shook off her growing irritation by silently reciting the mantra she and her best friend, Shonda, had developed while dealing with bitchy customers back at the Burger Barn in Ithaca. Think it. Don’t say it. She could imagine a giant swarm of flying piranhas busting through the front windshield and reducing Norah to a small mound of bone dust and a pair of pearl teardrop earrings. She simply had to smile politely while she pictured it.

When Bert drove by the ENTERING MANSFIELD, INC. 1770 sign, Edie recalled the last time she’d visited. It was more than seven years ago, back when her mom’s massive blowout with her sister led to a mutual boycott on family visits. Edie had been startled by her mom’s ferocity, and a little impressed, too. The two of them made a pinkie pledge that day to never enter Mansfield again. Now Edie was breaking that pledge. A little knot of guilt and grief formed in her gut. It tightened as the familiar landmarks continued to speed past: the ice cream shop, the library, the murky and probably polluted lake that Edie and her mom used to plunge into on hot summer days. Childhood memories flooded her, one after the other, rushing in faster than she could handle. She accidentally let out a sniffle. Then another.

Norah craned around from the front seat.

“Don’t sulk, dear,” she scolded, gentle but condescending. “Bashful, I can handle. Awkward, we can work on, but I can’t abide sulking.”

Edie wiped her nose on her sleeve.

“I was just thinking about my mom,” she said as the tears continued falling.

Bert flashed her a sympathetic smile through the rearview mirror. Edie gratefully returned it. Norah, true to character, took no notice of either of them.

“I understand a few tears,” she said, “but while you’re with us, please try to demonstrate a little moderation.”

“Moderation?” Edie asked, unsure how such a thing was possible. What was she supposed to do, cry every other tear?

Bert reached over and patted Norah’s hand where it rested on her lap.

“It’s only been three years,” he quietly reminded her. “And a girl onl

y has one mother.”

“I only had one sister,” Norah countered. “But at some point even Frances would want us to move on.”

Edie felt her temper rise, simmering under her skin like shaken soda-pop. She could handle being criticized. She’d prepared herself for endless disapproval, mandatory gratitude, and the uniquely tenacious agony of feeling like she’d never fit in. She’d even expected the ugly jolt of betrayal she felt for violating the pact she’d made with her mom. But she couldn’t believe Norah was putting a statute of limitations on missing someone. Then again, limitations had always been one of her specialties.

“I suppose a bit of moodiness is to be expected,” Norah continued with a sigh. “Frances was always so temperamental, and you know what they say about the apple.”

“It keeps the doctor away?” Bert snuck Edie a wink.

Norah shot him a glare.

“It doesn’t fall far from the tree,” she said.

Edie bit her tongue, desperate to prove Norah wrong about her temper. The task grew increasingly difficult when Norah failed to cease her censure, soften her put-upon sighs, or get eaten by flying piranhas. By the time Bert pulled the car into the long and winding driveway, Edie was ready to explode. A thousand words pressed at her lips, none of them polite. Her only solution was to bolt before she said something she’d regret.

The second Bert’s key turned in the lock at the side of the house, Edie ran past him, her old army duffel in one hand, the guitar case in the other.

“Where do you think you’re going, young lady?” Norah challenged.

“Somewhere I can sulk,” Edie snapped, the words flying out too fast to stop them. “In moderation.”

With that, she fled up the stairs, ran down the hall, and slammed the bedroom door behind her. She stood there for several seconds, battling her instinct to flee all the way back to Ithaca. Too bad that wasn’t an option. She’d agreed to move here. Papers had been signed. Legal guardianship had been transferred. For the next five months, until she turned eighteen and left for college, she was stuck in Mansfield.

She set down her belongings and reminded herself that the situation wasn’t all bad. Her aunt and uncle were offering her room and board, sending her to private school with her cousins, and making an effort to repair the family rift. Edie also appreciated having her own room, even if it was only on loan until guests arrived. She’d shared her last bedroom with two kids half her age. Her foster mother also snored like a stuttering sea cow, and the creepy building manager always waylaid Edie for small chat while he ogled her boobs. Surely a few months in Mansfield would be an improvement.

Edie crossed the room and flopped down on the enormous sleigh bed, jostling the dozen or so eyelet pillows that’d been carefully arranged to imply they’d been dropped at random. It really was a nice bed. She could get used to that, at least. She surveyed her surroundings as she tried to picture herself settling in. Aside from the excess of white, not much had changed since her grandparents owned the house and she used to visit with her mom. The antique furniture was perfectly matched and polished. The door handles were porcelain. The lamps were cut glass. Everything was either fragile, sterile, or both, leaving Edie terrified she was going to break or stain something. It was a nice house but it didn’t feel like home.

To Edie, home was safety, comfort, and a place where she could make mistakes because someone was there to help her laugh at them. A place where her seven-legged, bug-eyed caterpillar drawing stayed on the refrigerator years after the paper yellowed and the pipe cleaner antennas fell off. Where she and her mom read desperately tragic novels together. Where they shared Edie’s first cigarette, her first drink, her first post-heartbreak cry. Home was where Edie built memories. Home was where someone loved her. Here in Mansfield, Massachusetts, home appeared to have a more formal definition.

Edie took out her phone and opened the web page she ran with her best friend: Shonda and Edie’s Indispensable and Only Occasionally Illogical Lexicon. She posted a new entry.

Home

noun

A temporary refuge potentially preferable to foster care, homelessness, or Taisha Duncan’s lumpy pullout sofa bed.

A residence containing three marble fireplaces, four unused bedrooms, and two dozen sets of shiny black shutters that don’t actually shut.

A place where the doors are always open but the arms are not.

Edie stared at the screen, desperate to see a ping of connection with her friend. The comment section remained empty. She was starting to suspect Shonda had shut off her new post notifications, or, even worse, she was ignoring the site completely. With a pang of loneliness and an ache of uncertainty, Edie slipped her phone into her pocket and promised herself to check it only once an hour. Maybe twice.

She retrieved her mom’s guitar case and sat down at the dressing table that was wedged between two bay windows. A dressing table, she noted, not a desk. God forbid she do anything but prepare herself to look fabulous for the neighbors. With a sigh of resignation, she opened the case. Two things lay inside: a dog-eared notebook filled with Edie’s songs, and a stringless guitar, its surface scratched, its tuning pegs askew. One day, when the thought of playing no longer made Edie well up with tears, she’d buy some new strings and make the guitar sing again. In the meantime, she’d simply keep it close. It stored some of her favorite memories: following her mom around to open mic nights, writing songs together, dozing off to a lullaby about sleeping in a crescent moon.

Edie traced a line down the guitar’s neck as she recalled the first time she’d played her mom’s favorite song, “Water, Water, Wash Me Slowly.” She was only seven, barely able to hit all the notes. Her mom had practically burst from pride, telling everyone her daughter was going to be a huge star. That was a good memory. That was a hold-on-to-it-forever memory.

She was about to shut the case when her eye caught on the napkin that was poking out from her notebook. She slipped it out and smoothed down the wrinkles. It was mangled and stained, but the scribbled words were still legible. I can’t. I’m sorry. Move on. Edie’s dad had stuck the note to the refrigerator door with an inauspicious out-of-season Santa Claus magnet when Edie was still a baby. He disappeared that day, for good, but Edie’s mom kept the note, brandishing it whenever Edie mentioned boys.

“Edie,” she used to say, “never fall in love. As soon as you give a man your heart, he’ll shine his two-sided smile on someone else, trading his promises for your regrets.”

Edie had few worries on that front. As an outsider in Mansfield, she’d have a hard enough time just making friends. For the rest of the school year, she intended to bury her head in her books, hoping to keep up her grades and earn a scholarship. Then, in August, she’d walk in her mom’s footsteps—exiting the same house in the same town, also shortly after her eighteenth birthday—but Edie would be running off to college, not to a husband. Haunted by a scribbled napkin and a flickering sadness that used to pass through her mom’s eyes, Edie wanted an education more than a romance.

Mostly.

Chapter Two

* * *

Edie unpacked her meager belongings, stashing her wrinkled clothes where her relatives wouldn’t examine them too closely. She nestled a few personal items on her nightstand: a book, a mug, a photo of her mother. Just enough to feel a little more at home. As she slipped the guitar case under the bed, footsteps approached in the hallway, sounding vaguely like rhinoceri. Or rhinoceroses. Or girl-eroses. A second later her cousins burst into the room, a dizzying whirl of navy and green plaid uniforms, auburn hair, and floral perfume. All knees and elbows, and half a head shorter than her sister, Julia still looked like a child despite her sixteen years. Maria, now eighteen, was made of three things: voluptuous curves, catlike green eyes, and (provided nothing had changed over the years) the unfailing belief that she was superior to everyone around her.

“You’re finally here!” Julia sped across the room, arms outstretched, slamming into Edie with an eager em

brace. “You look exactly how I pictured you.”

Edie studied her cousin, trying to suss out if she’d just received a compliment or an insult. Julia simply grinned, offering no clear indication of either.

“You must be exhausted.” Maria spun Edie her way and gave her a big hug. “Didn’t you just have, like, a four-hour bus ride?”

“Something like that.” Something more like twelve hours, with all the stops, but Edie didn’t correct Maria. Maria had never cared much for being corrected.

“I hate buses,” she said with a sneer. “They smell like corn chips and BO.”

“Or Cheetos and BO?” Edie flashed her stained fingernails.

“Whatever. I didn’t mean you.” Maria plucked a few pills off Edie’s old golf sweater, demonstrating that she’d inherited her mother’s annoying talent for improving people. “We’re just glad Dear Mama finally stopped holding her stupid grudge and invited you here.”

“‘Dear Mama’?” Edie choked back a laugh. “Seriously?”

“She can’t stand it when I call her that. I use it whenever I can.” Maria continued picking and plucking, immune to the concept of personal space. “She said you were upset about leaving all your friends, and our hearts are shattered for you—like, a-million-tiny-pieces shattered. Being new is the worst, but we’ll make sure you’re never alone.”

“Um, thanks?” Edie shrugged, unsure how to explain that loneliness and aloneness were two completely different things. Since Maria had always been surrounded by friends and admirers, she was unlikely to understand either concept.

“We’re not allowed to let you sulk,” Julia added while straightening a row of tree pictures that didn’t need straightening. “It’s bad for the complexion. Whenever I cry I get all red and puffy. Maria says I look like a lobster balloon.”

“I do not.”

“You do too.”

“Then don’t cry.”

“Then don’t be a bitch.”

Julia marched over to the bed and plunked herself down, arms folded, lips pursed, indignation personified. Not much had changed since Edie’s last visit to Mansfield. Her cousins were merely a little taller, a little older, and a little less likely to fight about who was looking at the other one the wrong way. A little less likely.

Hearts, Strings, and Other Breakable Things

Hearts, Strings, and Other Breakable Things